There was the Hill of Howth, lying purple in the light. Dublin lay to the west, a dull ruby under a canopy of smoke. The sight fascinated Joyce. For a long time he gazed at his native town, ‘The Seventh City of Christendom’. [Gogarty]

Current Research Interests

POETRY AND RE-IMAGINING IN THE QUEST FOR SOVEREIGNTY AND SELF-DETERMINATION

Paper dedicated to Palestinian poetry, to be presented June 7, 2025

The Internal World of James Joyce

‘Thou are become (O worst imprisonment) the dungeon of thyself’ – [Milton]

The photo is of James Joyce, age 6, at Clongowes Jesuit boarding school outside Dublin where he was the youngest student.

I am interested in the fact that Joyce’s parents devastatingly lost their first child a year before he was born. Joyce spoke of being ‘exiled in on himself’ and felt himself an outsider—a feeling common in replacement children. This sense of dislocation is echoed in Portrait of an Artist, where he says about Stephen:

To merge his life in the common tide of other lives was harder for him than any fasting or prayer. He saw clearly his own futile isolation. He had not bridged the restless shame and rancour that had divided him from mother and brother and sister. He felt that he was hardly of the one blood with them but stood to them rather in the mystical kinship of fosterage, foster child and foster brother.

All his life he suffered from phobias, fears and superstitions:

His fear of dogs and thunder are no secret to us, his fear of madness he both admitted and repudiated, but his fear of aloneness he kept to himself. His family were a bulwark against it and so was drink. His eyes were so weak that long periods of his life were passed in a state of virtual blindness. (O’Brien)

About his writing, Colm Toibin gives the following description:

Joyce was concerned not with some dark vision he had of mankind and our fate in the world but rather with the individual self he named and made in all its particularity and privacy. The self’s deep preoccupations, the isolation of the individual consciousness, which keeps so much concealed, were what he wished to dramatise. The self ready to feel fear or remorse, contempt or disloyalty, bravery or timidity; the self in a cage of solitude or in the grip of grim lust; the self ready to notice everything except that there was no escape from the self, or indeed from the dilapidated city; these were his subjects.

The Artificer. James Joyce

By Padraic Colum

The long flight and asylum barely reached—

Asylum, but no refuge from afflictions

That bore on you and left you broken there—

This was the word was brought me: loneliness

That was small measure of the loneliness

That days and nights was with you, came to me.

Dedalus! Has your flight ended so?

I looked back to the days of our young manhood,

And saw you with the commons of the town

Crossing the bridge, and you

In odds of wearables, wittily worn,

A yachtsman’s cap to veer you to the seagulls,

Our commons also, but your traffic

Sombre: to sell your books upon the quay.

And then, with shillings flushed,

To Barney Kiernan’s for the frothy pints,

And talk that went with porter-drinkers there.

But you

Are also Schoolman, and these casual men

Are seen, are viewed, by you in circumstance

Of history, their looks, their words

By you affirmed, will be looked back on,

Will be rehearsed. Nor they, nor I

Nor any other, will discern in you

The enterprise that you in secrecy

Had framed—to soar, to be the man with wings.

Donald Meltzer

Life inside the Claustrum

An important contribution to our understanding of a persecutory inner world and the reality of internal space has been Donald Meltzer’s concept of the ‘claustrum’, described as the unconscious dwelling place of the pseudo-mature individual. Meltzer takes us right inside the internal world discovered by Melanie Klein giving a vivid picture of the geographical compartments of the phantasy internal mother:

The compartments resemble the divisions Hell, Purgatory and Heaven: in the rectum, the genital or inside the breast or head of the primal mother.

As he put it, “My contribution has consisted of an invasion of a space that is really a mythological space—the unconscious”. Klein, he says, tended to treat projective identification as a ‘psychotic mechanism’ which operated mainly with external rather than internal objects. Meltzer, who later described projective identification as ‘the most important and most mysterious concept in psychoanalysis’, saw this particularly intrusive kind as an essentially anal process (anal suggesting an expelling of unwanted bits of the self). He called it ‘intrusive identification’ to clarify the pathology involved and distinguish it from the kind of projective identification, which is an unconscious form of communication, described by Bion.

The Replacement Child

The term ‘replacement child’ is given to a child who lost a sibling, either before or after they were born. The loss of any child is traumatic for the family and, in their grief, parents may deprive the surviving child of the necessary containment.

Problematic in the internal world of the replacement child is the child’s imagination. As described by Melanie Klein, children have murderous phantasies towards mother’s other babies. If these phantasies coincide with the actual death of a sibling, the child is left afraid that wishes can become reality just by thinking them. In the psychoanalytic literature there are poignant accounts of patients who felt to blame for not having prevented a sibling’s death. Some believed they actually caused or should have prevented the death even though they had not yet been born.

Survivor guilt in the replacement child can leave them feeling they have no right to belong, that they are sentenced to a life of exile. It can also produce a paranoid inner world, reminiscent of the claustrum described by Donald Meltzer.

David Storey

You died six months before my birth. Everything I have made, and everything I have experienced, has been from within your shadow, the shadow not of your presence but of your death, a ready door, cajoling, at the centre of my mind.

Loss was to permeate everything. The vacuum of grief that your death had created was being exposed, and my attempts to deal with it abused.

The past came to me in vivid dreams: dreams of dying, or of being dead—of lying, in one instance, on a mortuary shelf: crawling off, refusing to succumb. Mourning the death of someone I had never known.

Like a rat its cage, a snail its shell, this canopy of terror.

Samuel Beckett

“James Joyce was a synthesizer, trying to bring in as much as he could. I am an analyzer, trying to leave out as much as I can. The kind of work I do is one in which I’m not master of my material. The more Joyce knew, the more he could. He’s tending toward omniscience and omnipotence as an artist. I’m working with impotence, ignorance”

Seán O’Casey

Seán O’Casey was full of admiration for Joyce and particularly for Finnegans Wake, which, he said, led him ‘into many a laugh and into the midst of wonder and wonderland’. But the war started a few months later and they never met. ‘Finnegans Wake is me darlin’, O ‘Casey recorded in 1940: ‘the dream is the world’s nightmare and the clap of thunder is in our ears once more’. Once more, because it echoed the thunderclap of World War I, re-echoed by that thunderclap in Dublin.

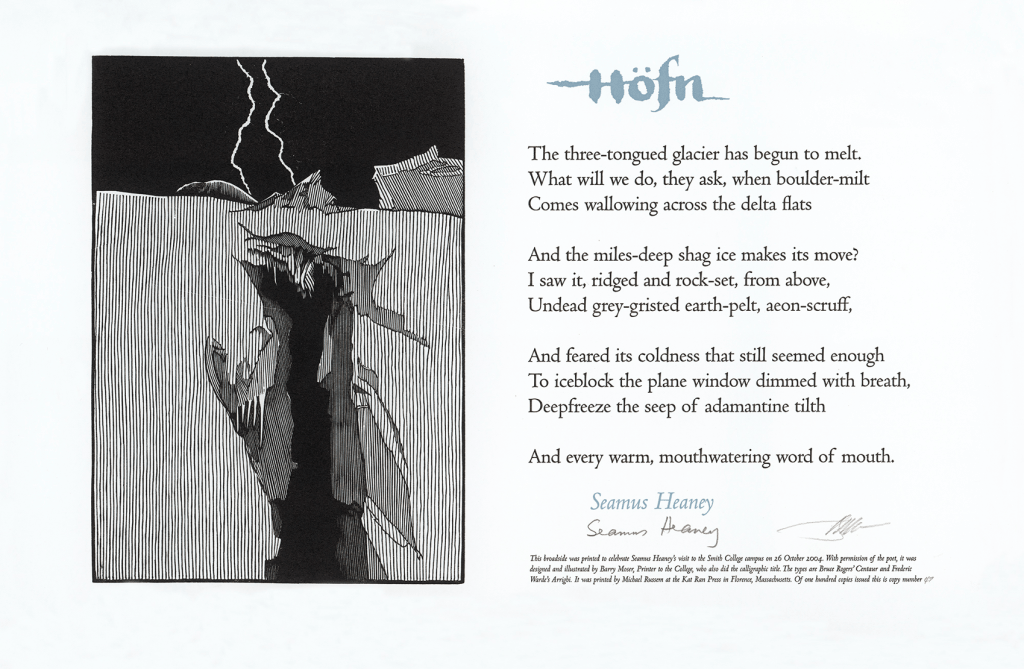

image: Leonard Baskin, 1952

Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney, his Lost Sibling and Re-Imagining

‘A white bird trapped inside me beating scared wings’

…pearls condense from a child invalid’s breath

into a shimmering ark, my house of gold

that housed the snowdrop weather of her death

long ago…

…It was like touching birds’ eggs, robbing the nest

of the word wreath, as kept and dry and secret

as her name, which they hardly ever spoke

but was a white bird trapped inside me

beating scared wings….